Editor’s Note: The Caprock Chronicles are edited by Jack Becker a Librarian at Texas Tech University Libraries. He can be reached at Jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article is by Holle Humphries, a retired art educator and the facilitator for the Quanah Parker Trail, a cultural heritage trail sponsored by the Texas Plains Trail Region of the Texas Historical Commission.

On May 24, 2014, Charles A. Smith headed south on FM 1054 to Gail, Texas, to install one of his 32-foot steel arrows to commemorate Quanah Parker’s last campsite as a nomadic Kwahada warrior. He led the way for three of Quanah’s great grandsons, Bruce, Ron and Don Parker, following behind, making a journey to this place they had not seen before with their own eyes.

Dropping off the Caprock, the road rounded a curve to the east, exposing suddenly a panoramic view of the Brazos and Colorado river watershed unfolding to a far distant horizon, with Muchaque Peak visible in the far distance, standing like a timeless sentinel guarding all.

Don Parker, with an intake of breath and awe in his voice said, “Oh, this is so Comanche.”

For the first time since Quanah’s departure, Comanche family members returned to this place, after 139 years, to dedicate an arrow installed to honor him.

From his birth, circa 1845 to 1852, to the year of 1875 when he accepted Colonel Randall S. Mackenzie’s ultimatum to come in to the reservation at Fort Sill, Quanah’s moccasins and the hooves of his horses criss-crossed the Llano Estacado, bison hunting and raiding. More than once he took the Comanche Trail to plunder Mexico.

Although uncertain as to where he was born, confiding to Charles Goodnight that tribal elders told him that he had been born on Elk Creek at the foot of the Wichita Mountains, Quanah regarded himself as “a Texas man,” as he wrote to the state’s governor in 1907. Indeed, the area alluded to by elders is known today as the Quartz Mountains of Greer County, lands which formerly belonged to Texas.

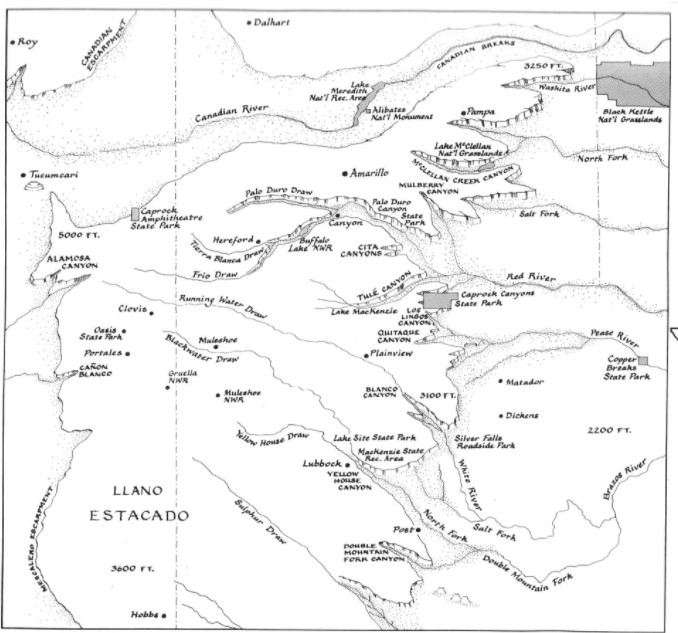

As a boy born into the Nokoni band, and later as a Kwahada warrior, Quanah traveled trails that followed the course of four major rivers, their tributaries and dry channel draws that drained the High and Rolling Plains: the Canadian, Red, Brazos, and Colorado. The latter three rivers originate in the Llano Estacado.

The rivers carved canyons that provided sanctuary and shelter from cold winter winds. The grasslands on the caprock above nurtured antelope and bison hunted by Comanches for food, clothing and shelter, and provided pasture for their horse herds, numbering in the thousands. On this flat and seemingly featureless plain, Quanah, like all Comanches, knew how and where to find water. Two campsites he favored allude to water: Roaring Springs in Motley county, and Silver Falls in Crosby county.

A snapshot of the extent to which Quanah ranged over this region when just a youngster, are revealed in an interview conducted by a Dallas newspaper reporter on October 9, 1905. While camping at Samuel Burk Burnett’s Four Sixes ranch in King county, Quanah “remembered as a boy passing through this country, on the old Indian Trail that passed by two mountain peaks one mile south of where Guthrie is located on the South Fork of the Big Wichita River.”

He also recalled the Croton salt flat twenty miles southeast of Guthrie on Salt Croton Creek that arises in Dickens county and flows westward across Kent county, and on to Brazos River. Fellow Comanches described “the old Indian camp grounds near where Guthrie now stands,” and noted this was the gateway for Indians in their raids east, south and southeast. They also rendezvous at [Tule] and [Palo Duro] Canyons.”

These canyons were cut by Tule Creek and the Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River, which flows through Randall, Armstrong, Briscoe, Hall and Childress counties, becoming the Red River and the northern boundary of Hardeman county, where in 1890 a town was named for him.

As a young warrior, Quanah accompanied the Comanche to the farthest corners of their ComancherÍa homeland. In the mid-1860s, he witnessed their convocation with the Utes to negotiate a peace treaty near present-day Dalhart in Dallam county.

After attending the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty proceedings in Kansas, he accompanied Kiowa chief Lone Wolf and traveled by mule, heading southwest across the Texas Panhandle over the Comanche Trail to raid into Mexico.

After Custer’s 1868 slaughter of the Cheyenne on the Washita River, Quanah and the Kwahada wreaked revenge beyond the Llano, striking deep into north central and far West Texas, past the line of forts intended to safeguard the frontier for Texas settlers.

After the raid, bearing plunder, he then followed the Trail of Living Water linked by the stepping stones of springs across the Llano Estacado, to travel west into New Mexico where he traded with the Mescalero Apaches.

This was well before 1871, the year Quanah first tangled with his greatest foe and respected adversary, Colonel Mackenzie, in the Battle of Blanco Canyon.

By then, in following long established Indian trails, Quanah already had crossed nearly every present-day county in our region.

For more information, visit: http://www.quanahparkertrail.com